“Selfitis”: No Selfie Control?

“Fantasy mirrors desire. Imagination reshapes it.” - Mason Cooley

The Selfitis Behavior Scale was created not to establish the practice of taking selfies as a mental disorder but rather to identify the psychological constructs underlying the practice (1). The researchers identified six components of selfitis: environmental enhancement (creating better memories), social competition, attention seeking, mood modification, self-confidence boosting, and conformity.

In another study, taking and editing the selfie resulted in increased negative mood and facial dissatisfaction (2). It appears that the editing of selfies might qualify as more than just a mere psychological construct.

Does selfitis have long-term consequences that create “no selfie control”? Could selfitis have both positive and negative influences on our psychological well-being?

Statistics

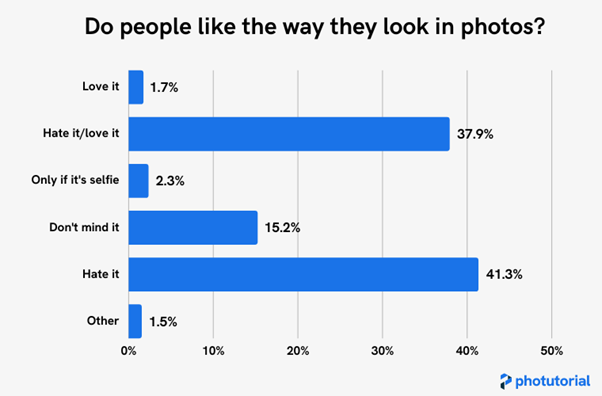

Looking at the statistics of selfie taking might provide a clearer picture of some of the primary issues.

18-to-24-year-olds reported that one in three photos they take is a selfie, while some confessed to taking more than 8 selfies daily.

1-4 selfies/day: 55.7% of participants.

5-8 selfies/day: 35.3% of participants.

8+ selfies/day: 9% of participants.

In regards to posting those selfies online:

0 posted selfies/day: 34% of participants.

1-3 posted selfies/day: 40.5% of participants.

3+ posted selfies/day: 25.5% of participants.

50%+ of millennials published a selfie.

Millennials, usually between 18 and 34, have been particularly drawn to selfies. More than half of young adults have posted a selfie to a social media website, compared to 24 percent of Generation X-ers and 9 percent of Baby Boomers, the Pew Research Center discovered last March.

People spend 54 hours a year taking selfies.

Respondents to the Luster survey said they took an average of nine selfies a week and put the average amount of time needed at seven minutes. According to the study, that adds to about 54 hours a year of taking selfies, including responses from 1,000 young adults (3).

The realization that so many people reported dissatisfaction with their selfies explains the perceived need to edit these photos. The extraordinary number of selfies being taken, and potentially being edited and posted, illustrates the obvious obsessional and possibly addictive potential that selfies represent.

Group Selfies

Selfies taken as part of a group, especially friends and family, can be all about experiencing a sense of belonging. These selfies are about the close connections in our lives. They represent a positive aspect of the power of the selfie. People can look back and celebrate good times together. These selfies are healthy experiences to be cherished and shared. They are, however, seldom edited to look better. Why is that?

Maybe because group selfies are not really selfies at all. They are just group photos like the ones grandma took. To be a selfie really is all about taking photos of just myself or just about myself, not about the others that may be in the photo. What does this tell me about selfies if this is true?

I only edit the selfie that represents the identity I see as not okay. When I finally post my selfie is that the self I see as okay? My selfie seems to be about my expectations of myself, which equates to more than my real or actual self.

Do I prefer my fantasy self to my real self? Is that affecting my sense of well-being? Are these healthy selfies?

“Unravelling external selves and coming home to our real identity is the true meaning of soul work.” – Sue Monk Kidd

Selfitis

Maybe what a selfie represents is my outside-in identity. This identity may be more palatable than what I see from the inside-out. The selfie then becomes an aid to my acceptance of my inside-out identity. Long term obsession with this artificial manipulation of my perceived identity may start to lose power and escalate to selfitis. I need more and more validation (through selfies) to shore up my fragile identity.

Fantasy or Real?

As the fantasy-self takes over, is the real-self displaced? What could be behind this fascination with a selfie identity? Could it be that there is a risk in being our real-self? Is there any fear of our real-self being rejected? Do we need the fantasy to protect us from other people knowing who we really are?

This curated self, my creation of who I am, insulates me from my insecurities. The edited selfie protects my emotional and physical vulnerabilities. I have a self-constructed identity shield.

How many endless hours are spent curating this image of self that I present to others, especially online? And, let me not forget that others are doing the same. Will they even notice how much time and effort I have put into my curated self? Maybe not.

One possible insight into the curated self to remember is that by hiding my vulnerabilities, I might actually be exposing them. After all, every identity issue I work hard to protect and hide telegraphs to others what I am fearful to show.

My mask will not protect me. Fantasy and hiding behind my curated self will eventually lose out to reality. And if not, I might actually lose myself (4).

References

1-Ersun Çıplak & Meral Atici (2021). The Selfitis Behavior Scale: An Adaptation Study, European Journal of Educational Sciences 8(2):1857-6036, July, 2021.

2-Marika Tiggemann , Isabella Anderberg, Zoe Brown (2020). Uploading your best self: Selfie editing and body dissatisfaction, Body Image, 2020 Jun:33:175-182.

3-Matic Broz (2024). Selfie statistics, demographics, & fun facts ([year]), Photutorial, May 31, 2024.

4- Bruce Wilson (2023). The Curated Self. Psychology Today blog, February 9, 2023.